What Aspects of Your Voice Can Be Passed Down Between Family Members? *

S ome years ago, I was invited by my then boss, Jann Wenner, the owner of Rolling Stone, to exist the lead vocalizer in a ring he was putting together from the magazine'due south staff. I had just turned 41, and I jumped at the opportunity to sustain the delusion that I was non getting sometime. "Sign me upward!" I said.

My chief attributes as a vocaliser included impressive volume and an ability to stay more than or less in melody, but I was strictly a self-taught apprentice. I had, for case, never washed a proper vocalization warmup, and had certainly never been informed that the frail layers of vibratory tissue, muscle and mucus membrane that brand up the vocal cords are as prone to injury as a heart-anile genu. So, on practise days, I simply rose from my desk (I was finishing a volume on deadline and spent viii hours a twenty-four hours writing, in complete silence), rode the subway to our rehearsal infinite in downtown Manhattan, took my place behind the microphone and started wailing over my bandmates' cranked-upwards guitars and drums.

The folly of this approach became clear to me a few weeks into rehearsals when J Geils Band frontman Peter Wolf, whom Jann had enlisted to perform a vocal, pulled me aside. "You lot don't have to sing full out in rehearsal, man," he said. "Save something for the show." I followed his communication, but by and so my voice had taken on a pronounced rasp. I wasn't concerned. I had suffered hoarseness in the past and information technology had cleared upwards. Plus, a petty vocal raggedness is never out of identify in stone'n'roll. Also, and mayhap most importantly, I felt no discomfort – so how could I accept hurt my throat?

I continued attention twice-weekly rehearsals and soon reverted to my old means – really singing harder, trying to put some of the old volume back into my vocalism, which was sounding weirdly dampened. I was also finding it hard suddenly to hit high notes, like the F above middle C in the Stones' song Miss You ("Ohhhhhh, why'd you have to wait so long?"). Reaching for it, my voice would suspension up into a toneless rattle, or vanish altogether. This began to concern me as the days ticked downward to our gig – a holiday party at a downtown dance gild, to which Jann had invited 2,000 of his closest friends, including a constellation of celebrities.

Singing is as psychological equally information technology is physical. Stress attacks the vocal appliance, tightening muscles that should remain loose and pliable, restricting breathing, endmost off the pharynx, paralysing the tongue and lips. I was experiencing all of these symptoms as I took my place, heart phase, in the glare of the lights, and began our opening number, the Beatles' vocal I'll Cry Instead, originally sung by John Lennon. It would seem a fiddling on the nose to suggest that Yoko, along with her and John's son, Sean, were looking up at me from the front end row, except they were.

Today, I can barely bring myself to listen to the CD of that concert, which Jann later presented to each band member as a memento. I wince at the tentative fashion I sing that "Ohhhhh" in Miss You, sneaking up on the note from below, sliding into it gingerly. I become there, sort of. But at what price? Past the terminate of the night, I was growling the lyrics to White Room similar information technology was a Tom Waits number.

A 3-day bout of laryngitis followed. Then I began speaking in a parched whisper. This eventually "improved" to a torn-sounding rumble. Iii months after the gig, I was still speaking every bit if my words were being stirred through gravel. But I was determined to believe the trouble would articulate upward – until an alarming encounter in the building into which I had merely moved with my wife and baby son. Belongings open up the elevator door for 1 of my new neighbours, a smile blond adult female, I pointed at the buttons and asked, "What floor?" Her grinning vanished.

"You've got a serious voice injury," she said. I demurred, only she cut me off, saying that she was a voice omnibus who worked with Broadway singers and actors. And she said that she could see, in my neck, the compensatory musculus movements I was making as I spoke. I was, she told me, straining the tendons, pressing them in against my vocalization box (or larynx), in a bid to compress my vocal cords and assist them create sound. "I bet your neck gets pretty sore," she said.

In fact, for weeks I'd been indelible a peculiar sensation in my neck, as if I had scalded the pare. "You're no incertitude straining other muscles, as well," she went on. "Nosotros use our whole body to sing, and likewise to talk. Abdominals. Hip flexors. Shoulders. Back. With an injury like yours, yous're working harder with all of them. You lot must be pretty tired past the terminate of the day." I had been attributing the strange, bone-deep exhaustion that afflicted me every evening to the stresses of new parenthood and finishing my book. Not the muscular effort of speaking.

She invited me to drop by her apartment, anytime. She could prove me some simple relaxation exercises that would help with the immediate symptoms. I hate presuming on neighbours, and knew that I would never avail myself of this kind offer. My wife shrugged and said: "At the very least, you lot ought to see a laryngologist, but in case it's … something else."

This caught my attention. I grew up in a medical family and was familiar with the euphemism "something else". She meant a growth. A malignancy. This had never occurred to me. My rasp was and so conspicuously the result of singing with Jann's ring – or was information technology?

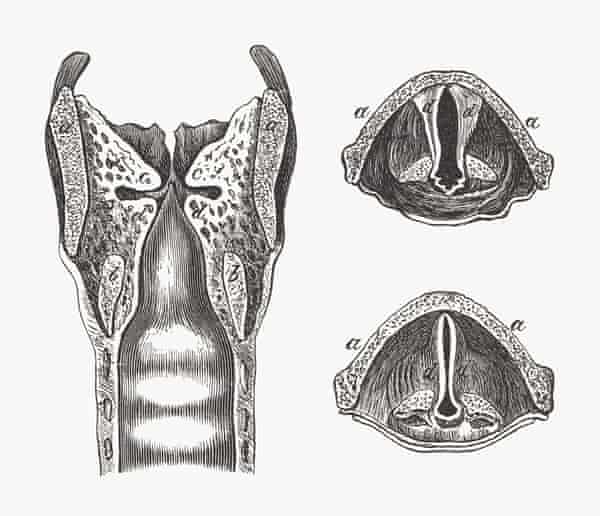

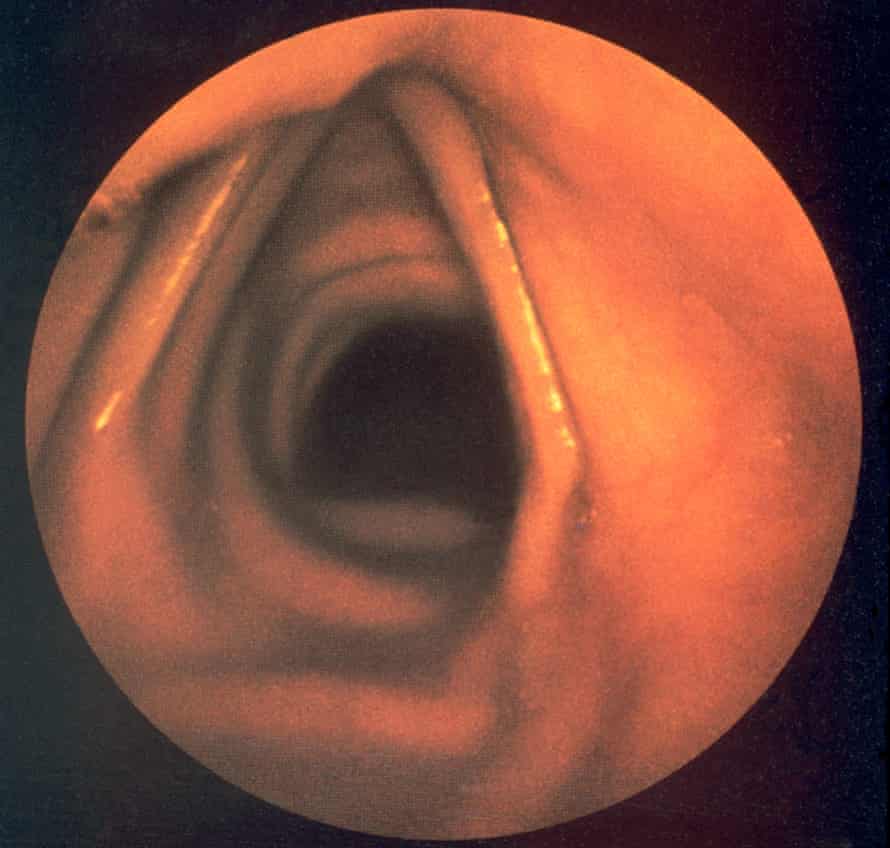

T he next day, I arrived at Mount Sinai hospital. I had an appointment with Dr Peak Woo, chief of laryngology, a subspecialty of ear, olfactory organ and throat medicine that focuses on the song cords. Woo was a soft-spoken man in his belatedly 40s with a kindly bedside manner. He guided downwardly my throat a laryngoscope, a tool that looked similar the curved spray attachment on a garden hose, with a small-scale low-cal affixed to the cease. On a nearby estimator screen, the live prototype of my pharynx was broadcast, a moisture red tunnel at the bottom of which sat my vocal cords: 2 symmetrical, fleshy, pearly-pink membranes stretched similar a pair of lips across the opening of my windpipe.

Woo pointed to the screen, which held a photograph of my vocal cords in the open position. It was not, he said, a malignancy. The edge of the left string was ruler-straight. On the margin of the correct cord was a small bump. A tumour would be lumpy, asymmetrical. My vocal mass was smooth and regular, every bit if a tiny pea had been inserted under the semitransparent mucus membrane: a textbook polyp, wholly consistent with my history of over-singing. I had broken a claret vessel in that vocal cord, and the unchecked bleeding had created the bump of scar tissue that was interfering with the vocal cord'southward normal, fluid, rippling activity. Sweet, pure singing voices are partly the result of vocal cords with clean straight edges that meet flush across the opening of the windpipe as they vibrate. Mine did non, and this is what produced the rasps and rattles and rumbles in my voice.

I asked if he might just snip the offending polyp off in a quick outpatient procedure. Hardly. To have the thing removed, I would need to check into the hospital for several days to undergo surgery, which would crave not simply a general anaesthetic but a special paraly agent to render me completely immobile – a crucial consideration given the extreme fragility of the vocal cords and the permanent injury to the voice that can result from removing even a micrometer besides much salubrious tissue.

I left his office with a prescription for a medication to have in the days earlier the functioning. Scheduling the procedure was up to me. He told me to call when I was ready. I never called.

Why? The usual excuses – no fourth dimension, too expensive, too risky and 6 weeks of strict postoperative song silence. Who could afford to stop talking for half dozen weeks? Similar most people, I took for granted the sounds that emerged from between my lips, thinking, as long equally I'chiliad getting the words out and being understood, my voice is fine. Which is not to say that I wasn't self-witting about my rasp.

Speaking on the phone, which ever heightened my awareness of my damaged voice, I ofttimes worried that I was conjuring in the brain of my invisible interlocutor the epitome of a thuggish underworld heavy – a particular business organisation if I was trying to get a potentially frail journalistic source to trust me. There was also the inconvenience of disabusing friends who mistook my rattle every bit a symptom of the influenza. Merely for all these annoyances and discomforts, I was not (I told myself) disabled. I could converse. I could work. By these lights, the surgery was not necessary.

I did, however, take certain measures to preserve what remained of my vocalisation. I concentrated on relaxing my neck, stopped pushing my voice out with an extra effort of my abdominals. This tended to reduce my volume – or "projection" – but it besides eliminated the scalding neck pain and overall burnout. I likewise learned, by unconscious trial and mistake, to lower my pitch, which seemed to smooth my tone a piffling.

Over time, I was even able to convince myself that the trouble had cleared upwardly – a state of denial I sustained for over a decade, until 1 twenty-four hour period in late 2012, when I started working on a new commodity for the New Yorker mag.

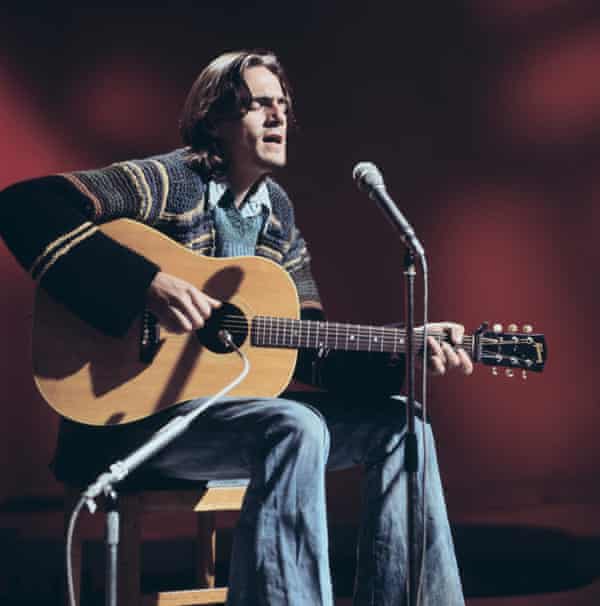

I t was about a vocal surgeon, Steven Zeitels, who worked at Massachusetts general hospital in Boston. Since the mid-90s, Zeitels had ministered to an array of pop singers – Steven Tyler, Cher, James Taylor – equally well as famous Tv set and radio broadcasters, opera stars, Broadway belters and actors. A few months earlier, he had successfully operated on the British vocaliser-songwriter Adele, removing a song polyp that had threatened to end her career. She had thanked him from the stage when collecting several Grammy awards.

When I chosen Zeitels to ask if he might be willing to cooperate with a story, I hadn't even finished my pitch before he interrupted me, saying: "It sounds like you're dealing with a pretty significant vocal upshot yourself."

Brought up short, I stammered something about having experienced "a lilliputian vocal strain" some fourth dimension ago, and changed the discipline. But I could not staunch his clinical marvel. When I visited Zeitels for our first prepare of interviews, he insisted on "looking at" my throat.

Like Woo, Zeitels peered into my pharynx with a laryngoscope; he, too, left an image of my song cords upwardly on his computer screen. Even to my untrained eye, the mass looked far bigger than in the photo taken more than a decade before by Dr Woo. Zeitels was certainly impressed. "You couldn't possibly sing with something this big," he said. "It'southward mechanically impossible." He was correct near that.

The few times I'd tried, my voice shut down, went off-pitch – and the extra exertion of driving air past my burdened vocal cord would force me to reload my lungs at an abnormally fast rate, making my phrasing choppy (good singers time their intakes of jiff around natural pauses in a song's lyrics), causing me to hyperventilate and abound silly. Trivial wonder that I had not sung publicly since Jann's political party, and no longer sang even in individual, around the firm. Too exhausting. Besides depressing.

Zeitels let me know, however, that my singing was non the primary effect. There was also the question of my speaking vocalization. Yes, I could still talk, he said, but my altered voice was affecting my life in ways that I was not acknowledging. "Hither'south the mode to understand your speaking phonation," he said. "You're grossly hoarse. People might say, 'Well, his vocalisation isn't that bad.' No. Your voice is really pretty bad. Your correct vocal string – the one with the polyp – has a severely impaired elastic dynamic adequacy. You're working at 3 or 4% of normal."

Consequently, he said, I had washed what many people with my injury do: I had adult strategies for, as he put it, "speaking around the trouble" – retraining my recurrent laryngeal nervus (the nerve that, among other things, controls the tension on the vocal cords) to drop the pitch of my voice, slackening my freighted vocal membrane so that the 3 or four% that was nonetheless pliable would vibrate. This reduced the rattle in my phonation, but at a cost. It was robbing me of the natural variation in pitch and volume that people use to give colour, animation, expression and personality to their utterances – what linguists call prosody, the melody of everyday speech communication.

Through prosody, we express tenderness, or anger, or enthusiasm, or any number of other nuanced emotional states that requite the homo vocalisation its peculiar power to woo, persuade, threaten, cajole and mollify. Prosody makes the difference between the affectless utterances of HAL, the figurer in 2001, and the rich and expressive instrument of Morgan Freeman or Meryl Streep – or fifty-fifty just the lilting, songlike way you say "Hello" when you respond the telephone, so your caller doesn't think you're a machine. The term comes from the aboriginal Greek: pros, meaning "toward", and ody, meaning "song". We speak toward song. Except I didn't whatever more than, according to Zeitels.

"You're behaving through a veil of monotone," he went on. "When you talk, you tin can't express emotion properly. You can't change pitch, can't get loud, can't do the normal things that a phonation does to limited how you feel."

This hitting me hard. I had not been consciously enlightened of these changes; but now that he pointed them out, I had to admit that my range of expression had indeed diminished. Though I could notwithstanding drive my voice through the basic melodic shifts necessary to make my emotional state more or less known, information technology had become burdensome to exercise so – too much expressive talking nonetheless left me pretty wiped out at the stop of a day – and my voice was by no ways the precision instrument information technology had one time been. More cudgel than scalpel, it would, when imbuing a word or syllable with special emphasis ("He said what?"), oftentimes pause up, or cutting out, altogether.

But that wasn't the worst of it. For Zeitels at present added: "You are not existence transmitted past your vox."

That the vocalization is a vital clue to character and personality – to central identity – was not news to me. I had always known that the voice is a kind of audible fingerprint, something unique to every individual and from which listeners describe strong inferences. Merely in "speaking effectually" that injury, I was patently projecting a new personality into the world: a more monotone, less enthusiastic, less engaged personality.

But my polyp wasn't just changing how others perceived me; information technology was actually changing my behaviour. "People with your type of injury withdraw from scenarios intuitively," Zeitels said.

"Y'all might have been brewing this polyp for decades earlier you lot sang in Jann's band," he added. "Wallflowers and introverts don't get this injury."

Feeling shaken, I said: "So – this changes my life, in a fashion?"

"Totally," he said.

T he vox is a deceptively unproblematic-seeming subject (you sing, you talk – big deal) that actually touches on some of the deepest mysteries in the natural globe: namely, how nosotros communicate thoughts, emotions, personality, upbringing and a lot of other personal data, on tiny ripples of air that nosotros beam into other people'southward brains past moving our lips and tongue while exhaling. An conflicting species watching united states of america perform this bio-lingual-psycho-acoustical feat would no doubt think: "This is unreal!"

And it is. Just how to become your hands around then large and diffuse a subject? In that location'due south a difficulty in even saying what the voice is. Is the voice singing? Talking? Is a coughing voice? A laugh? "Indeed, it seems we know exactly what we mean by the discussion voice as long as we don't effort to define it!" as Johan Sundberg, the world's foremost say-so on the physiology of singing, put it in the introduction to his archetype textbook The Science of the Singing Voice.

Aristotle, who defined the phonation equally "the audio produced past a creature possessing a soul", explicitly ruled out coughing as voice because a cough does not call up a "mental image" – that is, words. Unfortunately, that definition also rules out the high, clear sustained note that an opera tenor hits, and which sends shivers through u.s., despite the isolated vowel'southward calling up no specific "mental epitome" (particularly if we don't understand Italian). To say cypher of the fact that, in the 50s, a branch of spoken language scientific discipline called paralinguistics emerged, which convincingly showed that all style of vocal noises (coughs, sighs, gasps, ums and ers) can be highly revealing of a person'south inner land of mind and heart – and as such accept a communicative salience that, even past Aristotle'due south definition, qualify them as voice.

Add to these confusions the epistemological conundrum that the voice is, conceptually, impossible to "locate". Information technology is "in" the speaker'due south trunk as an act of breathing and joint, but doesn't exist until it is manifest in the air as a sound wave. Arguably, the vocalisation comes into existence, as vocalisation, only when someone is around to process that sound wave in the brain's auditory cortex. (In vocalism science, the answer to the philosophical riddle: "Does a tree that falls in a forest make a audio if there'southward no one to hear it?" is "No!") A concluding complication arises from the fact that what science calls the voice – everything from the buzzing audio source in our throats, to the way we sculpt that buzz into speech sounds with movements of our mouths, to the rhythm and melody of spoken linguistic communication or vocal – results from the synchronised actions of many distinct body parts (lungs, song cords, natural language, lips, soft palate), all of them originally designed (by natural selection) for quite different tasks. Which of these is the voice – some, all, none?

The key, I realised, was to recollect virtually what makes the human voice different from that of every other creature. All mammals and birds use vocal noises to communicate vital needs, through an array of oinks and squawks, chirps, barks and baahs. Parrots can even expertly mimic man speech – but without any idea what they're saying. We are the simply animal that can perform the miraculous feat of making the link betwixt a specific song sound and an object that exists in the world.

I telephone call it a miraculous feat, but that understates the case considerably. Information technology is the reason that we, equally a species, rocketed to the height of the food concatenation. If you've read Yuval Noah Harari's Sapiens, yous know that scientists usually aspect our rise to language, a kinesthesia that allows us to refer to events in the by or future, to allude to people and things not immediately present, to elucidate abstract philosophical concepts, and to make complicated plans and goals that we share with others of our species. No other brute tin come close to doing this. Birds, dogs, chimps, dolphins – you name it – use their voices to make in-the-now proclamations nearly immediate survival and reproductive concerns, including expressions of fear, anger, hunger and mating urges. Our unique ability for language has thus been described as the great dividing line, the "unbridgeable Rubicon", between us and every other living creature.

More than that, Harari says, it is the key to how nosotros came to dominion the Earth, since information technology enabled early humans – a relatively slow-running, physically weak, easily preyed-upon animal – to program and cooperate and strategise with each other to outsmart bigger, faster, more lethal predators, to organise into groups (or tribes) of a greater size than any other creature (chimpanzees, our closest animal relation and the next closest in terms of cooperation, can manage well-nigh 100 members per grouping), and eventually to build the villages, towns, cities and nations that have given united states primacy over the planet and everything on it. Written language eventually speeded this procedure upwards, merely that only came along nigh 5,000 years ago, a glimmer of the middle in terms of human history. Up until and so all verbal communication in our species was achieved via speech.

So, I'm non disputing the grand claims for linguistic communication fabricated past Hariri and others. I just think we need to refine the concept, to emphasise that we owe our planetary dominion not to language alone, but to our special talent for turning that awesome attribute into sound. The vocalism.

O ur career and romantic prospects, social status and reproductive success depend to an amazing degree on how nosotros sound. This is a question not but of our song timbre, which is partly passed down past our parents (in the size, density and viscosity of our song cords, and the internal geometry of the resonance chambers of our neck and caput), or our emphasis, but also our volume, pace and vocal attack. These elements of our speech betray dispositions toward extroversion or introversion, confidence or shyness, aggression or passivity – aspects of temperament that are, science tells us, partly innate, but as well a upshot of how we respond to life's challenges, in the innumerable environmental influences that mould personality and character and, consequently, our voice.

In listeners' ears, our voice is us, every bit instantly "identifying" equally our face. Indeed, researchers in 2018 discovered that voices are candy in a part of the auditory cortex cabled directly to the brain region that recognises facial features. Together, these linked brain areas make up a person-differentiating organisation highly valuable for ascertaining, in an instant, who we know and who's a stranger.

The voice recognition region can hold hundreds if not thousands of voices in long-term memory, which is why you can tell, within a syllable ("Hi … "), that information technology is your sister on the phone and non a telemarketer, and that an impressionist is attempting to "practise" Bill Clinton and not Ronald Reagan (both of whose voices you lot can conjure in your auditory cortex as readily equally you tin remember their faces in your heed's heart).

That we practice, sometimes, mistake family members for i some other over the phone shows that not only are immutable anatomical attributes of voice (vocal cords and resonance chambers) equally heritable as the facial features that make parent and child (or siblings) resemble each other, only that families oft share a manner of speaking, in terms of prosody, pace and pronunciation. But the vocalization of every person is sufficiently unique, in its tiniest details, that such misidentifications are usually caught within seconds.

Indeed, it is a philosophical irony of cosmic proportions that the just voice on Earth that nosotros do not know is our own. This is because information technology reaches us not solely through the air, but in vibrations that laissez passer through the hard and soft tissues of our caput and neck, and which create, in our auditory cortex, a audio completely unlike to what everyone else hears when we talk. The stark difference is clear the first time we listen to a recording of own voice. ("Is that actually what I sound like? Turn it off!") The distaste with which so many of us greet the sound of our actual voice is not purely a affair of acoustics, I suspect. A recording disembodies the voice, holds it at a altitude from us, so that we can hear with pitiless objectivity all aspects of how we speak, including the unconscious ways we manipulate prosody, pace and pronunciation to create the voice we wish we had.

When I mentioned this to a friend, he grimaced at the memory of hearing his recorded vocalism for the beginning time. "God!" he cried. "The insincerity!" He was reacting to the mismatch between who he knows himself (privately and inwardly) to be, and the person that he seeks to project into the world. All of u.s. practice this, quite unconsciously, and until we hear ourselves on tape, we remain mercifully deafened to how we perform this ideal self, in a bid to "put ourselves across", to make an impression.

The enterprise of being human is to carve out a congenial place to occupy in the globe, an accomplishment that we know intuitively depends to a frightening extent on how our voices audio in the ears of others. To modify your vocalism in ways that arrange improve to the person y'all feel yourself to exist, or that you wish you were, ways changing, fundamentally, who yous are.

This is an edited extract from This Is the Voice by John Colapinto, published by Simon & Schuster and bachelor at guardianbookshop.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2021/jan/19/vocal-polyps-injury-singing-john-colapinto-steven-zeitels

0 Response to "What Aspects of Your Voice Can Be Passed Down Between Family Members? *"

Publicar un comentario